Written By: Terence P. Stewart

Stewart and Stewart

Washington, DC

The Obama Administration is pushing hard to bring the Trans-Pacific Partnership ("TPP") negotiations to a conclusion, holding a day-long briefing of cleared advisors in Washington on February 11th and with TPP ministers meeting in two weeks following various intersessional meetings next week.

At the same time, the United States and the EU have started their talks on a possible transatlantic agreement (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership ("T-TIP")) with Ambassador Froman and Directorate General for Trade De Gucht meeting in Washington next week to gauge progress and the path forward.

There is little doubt that the two negotiations are critically important for the United States and the future direction of trade policy. TPP involves major countries on both sides of the Pacific – Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Peru, Chile, Mexico, and Canada in addition to the United States. Korea is in the process of trying to join the group, and other countries have indicated a possible interest, including China and Taiwan and possibly Indonesia and Thailand. And the United States and the EU are the two largest developed economies (or in the case of the EU, group of economies).

So it is not surprising that there is extreme interest in many circles in the United States on the negotiations. Understandably, different groups are primarily focused on the aspects of the negotiations that are perceived as directly affecting them and their interests. However, these two potential agreements are unusually critical because of the implications for the economy overall and our persistently huge trade deficit. Stated differently, if TPP and T-TIP are able to address in fact the underlying causes of the trade imbalances we have with these major countries, much of the trade imbalance can be addressed, adding millions of manufacturing and agriculture jobs here at home. If the agreements do not address effectively the pressing issues that drive the imbalance in our relationships, we will have established agreements that will perpetuate and could significantly aggravate the massive trade deficits.

While not articulated in all cases by the forces for and against the agreements and Trade Promotion Authority ("TPA"), there can be little doubt that these two agreements will be outcome determinative in many ways for the U.S. economy. Hence the need for the agreements to be balanced in fact to permit the resolution of the long-standing imbalances with these important trading partners.

Why these potential agreements matter so much.

In an earlier Trade Flow, I reviewed the fact that since the first trade promotion law was passed (Fast Track authority in the Trade Act of 1974) our trade balance in goods had gone from balance to huge deficits, amassing a total deficit in goods trade of some $12 trillion from 1975-2013 (around $9.5 trillion in goods and services).

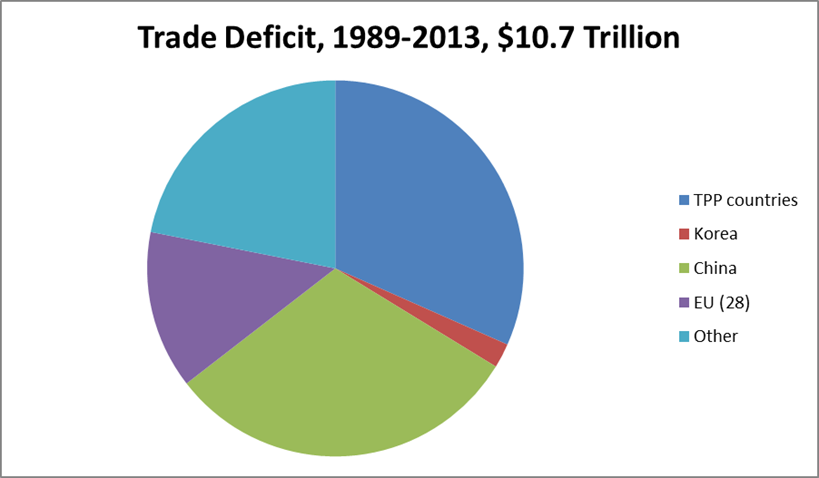

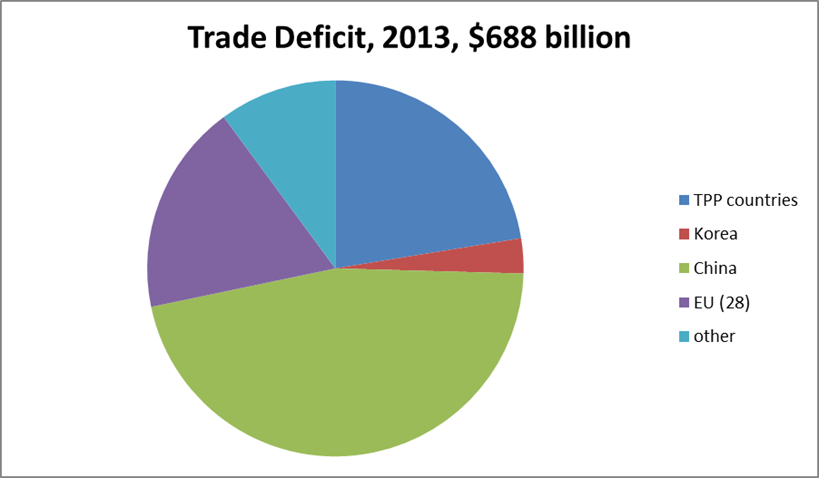

Since 1989, the U.S. deficit in goods has been $10.7 trillion and, as the annual data in the earlier trade flow showed, the deficit has grown in each Presidential administration since the 1970s. Of the $10.7 trillion, $3.4 trillion is accounted for by the 11 existing TPP members; Korea, has accounted for an addition $225 billion; and China for $3.3 trillion by itself. Similarly the EU (28) has amassed a trade surplus against the United States of $1.5 trillion since 1989. Thus, the existing TPP countries and the EU have accounted for 45.21% of the accumulated trade deficit since 1989. If Korea and China become members (Korea is likely; China is far less clear and certainly not immediate), the total becomes 78.10% of the trade deficit in goods. For 2013, the results are even larger, as the total is roughly 90% (89.90%) of the total trade deficit in goods.

While FTAs clearly increase trade flows in both directions and should thus improve consumer choices and competitive markets, imports can increase much more quickly than exports leading to significant net job losses in the economy. At the same time, trade liberalization can result in sharp downward pressure on wages and the pursuit of less than optimal environmental approaches to collective production amongst trading partners. The United States' experience with prior FTAs is objectively mixed, with some major agreements such as NAFTA and the U.S.-Korea FTA leading to growing deficits (Korea in its first year so far) and hence major job losses for the U.S. economy, while others have led to better trade balances for the United States and hence improved employment opportunities (e.g., Singapore, Chile, Peru, Australia). Private sector observers are thus anxious that any new agreements be likely to actually be positive for the United States on all aspects – trade flows, employment, standard of living, environment. Lack of transparency in the talks is obviously a major concern to members of Congress, their staff, and private sector interests, all of whom have complained of the limited ability to understand what is or is not happening and being addressed.

Will the agreements deal with the main causes of the deficit?

Unfortunately, for all of the topics that are being addressed within the negotiations, there are a few issues of greatest concern to correcting trade imbalances with the countries involved in the TPP and T-TIP negotiations (or potential TPP additions) that are not likely to be resolved through either set of negotiations.

TPP

In the TPP talks, while texts are not available, it is unlikely that there will be strong restraints on state-owned enterprises or meaningful enforcement of any obligations on transparency and fair dealing. There have not been in the past and press reports indicate strong push back from a number of the existing TPP countries on the topic.

Nor is there likely to be any meaningful provisions to address and correct currency manipulation/misalignment problems that the United States has faced with China, Japan, and Korea, amongst others, over recent decades and which some economists have suggested accounts for as much as 50% of the U.S. trade deficit. While such issues should be addressable within the IMF and/or the WTO, the IMF has been toothless in fact on these issues and successive Administrations have been unwilling to pursue challenges in the WTO or address them through domestic legislative remedies. Nothing in the media indicates there is any likelihood of a strong approach to this issue absent Congressional action.

For some countries, like Japan and Korea, long-standing issues that distort competition in important sectors like automotive have not been resolved despite (in the case of Japan) decades of bilateral talks and Administration efforts. While the United States is again trying to address the automotive issue with Japan (and will with Korea), there is no indication that meaningful progress in fact will occur or that either country will be denied participation if the issues are not finally resolved. Nor even if some resolution is included is there likely to be any meaningful automatic enforcement mechanism to actually obtain results that reflect whatever rhetoric is included.

For potential TPP members in the future, like China, entry into the WTO (where China made commitments to open markets but trading partners did not) resulted in large increases in exports to China that were dwarfed by increased exports from China supported by state policies preferring and protecting state-owned and invested enterprises, massive state subsidies, and a myriad of non-compliance issues with commitments undertaken including local content requirements, forced technology transfer, export restraints on various raw materials, etc. So while two-way trade has increased dramatically since accession, the U.S. trade deficit with China has grown by some $235 billion per year so that by 2013 it was at $318 billion – 46.3% of the U.S. total. In 2013, U.S. imports from China were $440.4 billion and U.S. exports to China were $122 billion – an extraordinarily lopsided relationship (78.3% of total trade is imports from China; just 21.7% of trade is exports to China from the United States). China has relatively low tariffs on many products at the present time and has shown no willingness to actually improve its level of compliance with WTO obligations. Thus it is hard to understand how having China join TPP at any point in the future under the likely terms being negotiated with the current group of countries will do anything but further exacerbate our trade imbalance and hence worsen the loss of manufacturing jobs and environmental challenges. While China is not presently part of the TPP process, it is important that the Administration and Congress ensure that the agreement addresses the issues that affect trade flows for all major countries in the Pacific region so the tendency to expand membership does not present challenges in terms of needing to renegotiate the framework with all members.

While all of the above issues (and the indirect tax issue reviewed below as part of T-TIP) could be addressed and resolved if actually pursued, seeking conclusion of the negotiations where such issues have not been resolved conflicts with the likelihood of actual resolution. Only Congress through its actions on TPA can help see that the TPP talks actually provide a balanced outcome needed by our country. Congress has done a good job of identifying currency manipulation as an issue needing resolution. It must step up on the other critical issues as well for the agreement to address the pressing issues of the day.

T-TIP

While the United States and the EU are focused on regulatory differences between the two areas, the massive trade deficit we are running with the EU is also due in significant part to the WTO's differential treatment between direct and indirect taxes, such that the EU (which has value added taxes ("VAT") of 15-27%) is able to rebate such taxes on goods exported to the United States and assess such taxes at the border on imports. The result is that the United States has no remedies for the large subsidies provided by the EU on exports (the United States has no federal indirect tax system and the rebate of indirect taxes on export has been excluded by the GATT and now the WTO from subsidy disciplines for decades) and our exporters face large taxes on importation. This issue is important in TPP as well, although the rate of indirect taxes is not as high generally as in the EU. Indeed, the combination of customs duties and indirect taxes faced by U.S. exporters who ship product to the EU has changed little since the late 1960s despite sharp reductions in customs duties both in the EU and in the United States. In 2007, our firm prepared a detailed review of the problem in a research paper to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Commission, "More Than 50 Years of Trade Rule Discrimination on Taxation: How Trade With China is Affected," Trade Lawyers Advisory Group, Terence P. Stewart, Eric P. Salonen, Patrick J. McDonough of Stewart and Stewart, August 2007. On page 12, we provided the following table and chart, which are self-explanatory: tariff and VAT rates when combined were 23.84% in 1968 and were 23.74% in 2001 (after tariff reductions from the Uruguay Round).

|

EU Tariff Rates and VAT Rates: 1968 – 2001[1] |

|||||

|

1968 |

1973 |

1988 |

1996 |

2001 |

|

|

Tariff Rates |

10.4% |

6.6% |

5.8% |

5.4% |

4.5% |

|

VAT Rates |

13.44% |

15.01% |

18.54% |

19.11% |

19.24% |

|

EU-25 Countries with VAT |

3 |

11 |

15 |

24 |

25 |

Without a harmonization in approach on this critical issue or the elimination of the differential treatment, the United States is peculiarly penalized in its trade with the EU.

Since President Johnson in the late 1960s, the United States has attempted to get the discriminatory treatment within the GATT and now WTO addressed. The effort was significant in the Johnson Administration and has been little more than pro forma for the last four decades, although it has been included as a negotiating objective in every fast track or trade promotion act. Congress looked closely at whether to adopt a VAT-type system in the 1970s and 1980s but faced overwhelming opposition from both the left and right to such an approach. Thus, the United States is the only major trading system without border adjusted taxes, hurting our domestic producers and their workers and communities as we face heavily subsidized import competition which cannot be addressed and face essentially higher border duties/taxes hurting our international competitiveness.

There is no indication that the indirect tax issue is being addressed bilaterally with the EU as part of T-TIP, a major mistake since the EU's VATs are so large and hence the distortion is so large. But any T-TIP where the underlying problem has not been addressed either through the WTO or in the bilateral agreement will doom the United States to continued large trade deficits with the EU driven by the tax distortion.

We have been unable to move our trading partners in the WTO (and GATT before it) and have been unable to change our domestic law to resemble that of other trading nations. Perhaps a bilateral or WTO solution of permitting rebates only to the extent subject to indirect taxes on importation and subject to assessment on importation only to the extent rebated from the exporting country would be an option that prevents double taxation without distorting the playing field for countries that do not use indirect taxation as a major source of taxes.

Again, while the indirect tax issue is most distorting between the United States and the EU, U.S. producers and their workers are also disadvantaged (typically to a smaller extent) by the same problem in countries who are part of the TPP negotiations and including those countries who may join.

Conclusion

The United States has done many FTAs in the past and is understood to be using the texts from such agreements as the building blocks as it looks to the TPP and T-TIP negotiations plus adding additional items. What is clear from the worsening trade flows with the group of countries being negotiated with and being considered for the TPP and T-TIP is that these agreements are too important to the resolution of our unsustainable trade deficit levels not to achieve concrete solutions to the underlying core issues.

Some of the critical issues are being discussed although there are no reports of significant progress in their resolution. Others (e.g., treatment of indirect taxes) are not known to be on the agenda in either negotiation. Obviously there is no chance to resolve such issues if they are not part of the negotiations in fact. The Administration must see that all these issues are addressed in fact even if that means some delay in the final resolution.

Moreover, history has shown that tools that promise compliance with negotiated agreements only work if they are automatic or at least not subject to political "restraint." Some countries, because of internal interests, serious differences in economic systems, or other reasons, end up having large numbers of issues where compliance is not occurring and where resolution is put off or subject to bilateral discussions, which means non-compliance extends for years or even decades. The recent USTR report on China's compliance with its WTO obligations is the most obvious example of problems that drag on for years unresolved despite ongoing "discussions," but the decades of problems with Japan in autos and the more recent challenges with Korea in the same sector have adversely affected large parts of the U.S. industrial base for far too long without resolution and without agreements that achieve the results intended.

As the countries at the table or likely to be at the table for these two deals constitute 90% of our current trade deficit – and hence have cost our economy at least 3.3 million jobs in 2013 of the 3.7 million lost that year through the trade deficit in goods – ensuring reciprocity in fact will have a lasting benefit to the United States and to the international trading system overall by making trade growth sustainable.

A good deal, which must address the critical issues causing the current distortions, will be a lasting legacy to the Obama Administration. Proper Congressional oversight and insistence on reciprocity not just in agreement language but in results will ensure that Congress safeguards the interests of all Americans and its own critical role in the formulation of trade policy. Greater transparency will ensure support from the American public, who will have a better understanding of what is being pursued and achieved and prevent the all or nothing sentiment that secrecy and a fait accompli approach to disclosure presently fosters.

One can hope that the missing issues of importance to address the lack of reciprocity that exists in fact will be addressed in the TPP and T-TIP negotiations despite the current status of the talks. If not, the United States will once again have failed to deliver trade agreements that actually promote true reciprocity. There may not be many more opportunities.

For more information about Washington D.C. law firm Stewart and Stewart, please visit the International Society of Primerus Law Firms.

[1] Data sources for Table and Chart:

Tariff Rates: For 1968 & 1973: simple average MFN tariff rates on industrial products applied by EU countries. See P. Hoeller, N. Girouard & A. Clecchia, The European Union's Trade Policies and Their Economic Effects, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 194, OECD ECO/WKP(98)7 (1998) at 22. For 1988, 1996 & 2001: simple average MFN tariff rates applied by EU countries on imports of non-agricultural and non-fuel products in 1996. See UNCTAD Handbook of Statistics, available at http://stats.unctad.org/

Handbook/TableViewer/tableView.aspx.

VAT Rates: simple averages of standard VAT rates in effect in EU countries in the relevant year. See European Commission, VAT Rates Applied in the Member States of the European Community, DOC/1829/2006 (Sept. 1, 2006), available at http://stats.unctad.org/Handbook/TableViewer/tableView.aspx.

EU-25 Countries with VAT: based on the year of VAT adoption for each of the EU-25 countries. See R.M. Bird & P. Gendron, VAT Revisited: A New Look at the Value Added Tax in Developing and Transitional Countries, USAID (2005) at pp. 167 – 169.